EQUINE GASTRIC ULCERATION SYNDROME (EGUS)

Gastric ulcers can present in a number of different ways, which can make them quite tricky to diagnose! Some of the signs your horse might show are:

- poor appetite

- weight loss

- poor performance

- poor body condition

- poor coat condition

- resenting the girth being done

- apparent back pain

- altered behaviour when ridden

- yawning

- dull demeanour

- mild recurrent colic

It is essential your vet takes a thorough history and performs an examination as many conditions can cause symptoms like these!

The Horse’s Stomach

Horses are ‘trickle feeders’ which means they have evolved to be eating forage for 18 hours every day! Their stomach constantly produces acid, which is normally balanced by lots of alkaline saliva production from lots of chewing. If your horse is not chewing, he is not producing saliva, leaving the stomach very acidic. Intense exercise decreases blood flow to the stomach, it also causes compression of the stomach resulting in acid splashing and contact with the non-protected part of the stomach. Both of these increase ulceration development. Stress and travel also have physiologic effects that make the stomach more acidic, and therefore predispose to ulcers.

Horses have two different linings in their stomach, the upper part is a squamous lining, which can develop ulcers due to excess acid exposure in this area (this is the non-protected area). The lower part is a glandular lining, which can develop ulcers when the protective mucosal barrier is compromised. The exact cause of glandular ulcers is less understood, further research is currently being carried out. The majority of ulcers occur in the squamous part.

Diagnosis

Once your vet has done a thorough exam and thinks ulcers are a definite possibility in your horse, the only way to diagnose them is by performing a gastroscopy. A gastroscopy involves hospitalising your horse and starving them overnight. The horse is then sedated and a special camera placed up through the nose, down into the stomach. This enables us to clearly see and evaluate the lining of the horse’s stomach. Starving your horse is important because if the horse ate all night all we would see would be chewed up food!

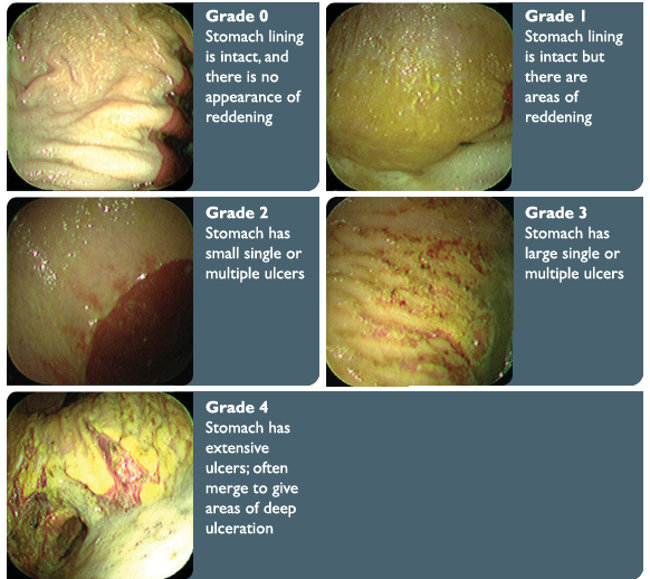

We grade the squamous lining of the stomach on a scale of zero to four depending on the severity of the ulcers:

http://www.equinegastriculcers.co.uk/what_are.html

An exact grading system has not yet been validated for glandular ulcers so we tend to just describe them.

Treatment

A treatment plan is then developed based on what is seen with the gastroscope. The mainstay of medical treatment is omeprazole, which is a proton pump inhibitor and the only licenced drug to treat equine ulcers. This reduces acid being produced by the stomach lining. Sometimes your horse may be given antibiotics and another drug called sucralfate, which protects the mucus layer of the stomach, although these are rarely used. A treatment plan is tailored for each horse individually by your vet.

Management and Prevention

As part of treatment and future prevention it is important to maintain a healthy pH in your horse’s stomach.

- Feed lots of forage, ie hay, haylage and grass. Horses have to chew forage before swallowing which means they will produce lots of saliva which will balance the acid in the stomach.

- Constant turn out has been shown to be very beneficial in preventing future bouts of ulcers as your horse has constant access to forage and stress is minimised.

- When stabled, feeding a range of forages is ideal as they leave the stomach at different rates, ensuring there will be some forage in the stomach for most of the time.

- Feed a small chaff meal before exercise to decrease acid splash.

- Adding vegetable oil to your horse’s feed helps as it slows the rate that food leaves the stomach.

Once correctly diagnosed ulcers can be relatively straight forward to treat. It is important to remember that the same symptoms can show in a number of conditions so it is essential to have a thorough investigation with your vet before performing a gastroscopy.

Please do not hesitate to contact your vet if you are concerned about your horse, or would like more information.